| 2005 |

|

YEAR BOOK |

Queen's University Belfast

|

What lies beneath: how geoscience aids criminal investigations

|

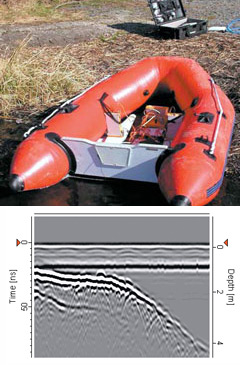

Recent criminal cases such as the murders of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman relied on evidence provided by geoscientists. So how can we assist in criminal investigations? The School of Geography at Queen's is currently focussing on the geophysics of graves, the detection and excavation of illegal toxic waste dumps and the spatial analysis of criminal activity using Geographical Information Systems (GIS). Ground penetrating radar (GPR) is often used in forensic geophysics as its success does not rely on metallic objects. Most GPR applications have been over loose ground (Ruffell & McKinley, 2004 1 ). However, we have been deriving data in freshwater environments in order to better inform the searches for victims of drowning and body deposition ( Figure 1 ). GIS is used to analyse crime patterns at various scales, with a view to prediction and police resources. Other social factors such as street layout, housing type, and deprivation can be combined using GIS to assist planners.

Reference:

1. Ruffell, A. & McKinley, J. 2005. Forensic geoscience: applications of geology, geomorphology and geophysics to criminal investigations. Earth Science Reviews, 69, 235-247.

Contact: Dr Alastair Ruffell or Dr Jennifer McKinley,

School of Geography, Queen's University, Belfast;

E-mail: [email protected]