| 2005 |

|

YEAR BOOK |

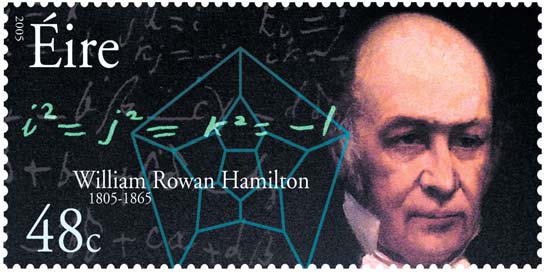

History of Science

|

What is an Irish Patriot?

|

How many of the youngsters, and those not so young, who have manipulated the actions of the curvaceous Lara Croft in Tomb Raider have appreciated the Irish input to her movements � for it is mathematics derived from Hamilton's work which makes Lara look (reasonably) human in her adventurous movements.

If, though, you ask those youngsters to name an Irish patriot, it is a fair bet that Hamilton wouldn't be the first name to spring to their minds. Most older people would perhaps be even less likely to choose him as a typical example.

There are, of course, some scientists who would qualify as patriots in the common understanding of that term � that is those who took an active part in the many episodes of the 'fight for Irish freedom'.

One of these, who was a participant in the 1798 rebellion, was William James MacNeven (1763-1841), who is credited as the 'Father of American Chemistry'. He was imprisoned but submitted to banishment for life and he ended up in America on 4 July 1805, where he distinguished himself to such an extent that he is commemorated by an impressive monument in St Paul's churchyard in New York. The inscription on the monument, in part, states that he: 'in the cause of his native land sacrificed the bright prospects of his youth and passed years in poverty and exile; till in America he found a country which he loved as truly as he did the land of his birth. To the service of this country which had received him as a son he devoted his high scientific achievements with eminent ability'.

How many people know that Robert Emmet (1778-1803) showed real promise in chemistry and mathematics when a student in Trinity College? Even before this, he had built a laboratory in his father's house so that he could carry out his experiments, and he nearly poisoned himself in the process. But he was compelled to abandon his scientific and other studies at Trinity in order to escape arrest for his subversive activities. He went on to be the leader of the abortive uprising of 1803, becoming a romantic folk hero in the process. His love for Sarah Curran (1782-1808) is one of Ireland's great love stories. As Thomas Moore (1779-1852) put it in his song, 'She is far from the land where her young hero sleeps': 'He had lived for his love, for his country he died, They were all that to life had entwin'd him'. Robert Emmet was tried, and sentenced to death for high treason, impressing with his bravery and eloquence in his speech from the dock. He was hanged and then beheaded at Thomas Street, Dublin, on 20 September 1803 at the age of 25. Had things been different, though, he might be remembered to-day as a famous Irish scientist.

Another scientist, who was involved in the 1848 rebellion, was Thomas Antisell (1817-1893), who was obliged to exit his native land and who also distinguished himself in America. He was chemist to the Department of Agriculture and the Patent Office there, he taught chemistry and other subjects at Georgetown University and at the University of Maryland. He was offered the presidency of Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, PA, and the University of Cairo, but didn't accept either. He took an active part in the American Civil War, as a medic on the Union side, attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was noted for his reckless disregard of personal danger for himself or his assistant surgeons.

A more-recent patriot, whom I actually met, for he taught me carbohydrate chemistry in Trinity College, was Tom Dillon (1884-1971). He was married on Easter Sunday morning, 1916, to Geraldine Plunkett, sister of Joseph Plunkett (1887-1916), one of the signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Dillon had been acting as a chemical adviser to the Volunteers on the production of explosives and hand grenades. After their wedding, the couple took a room in the Imperial Hotel opposite the GPO in Dublin. What Dillon hadn't realised was that the GPO was to be a major battle-ground. His role was to have taken charge of chemical works that the rebels intended to commandeer. As we know, the rising didn't take place as expected on Sunday and, on Monday, when it did, no chemical factories were taken. While Dillon escaped immediate arrest, he was eventually imprisoned in the City of Gloucester Gaol in 1918. As he put it himself:

|

One May night of that year, I was served by the Chief Secretary of Ireland, Mr. Shortt, with a notice, which, in my case he did not take the trouble to sign, that, whereas I was suspected of behaving, or being about to behave, in a manner prejudicial to the defence of the realm, he therefore ordered that I was to be detained during His Majesty's (or somebody's) pleasure. In the small hours of the morning, I found myself on a sloop of the British Navy in Kingstown (as it then was) Harbour with a goodly company. We were soon on our way to English gaols, where those of us who did not escape or die in the 'flu epidemic remained until the end of the following March.

|

On his release, Dillon was appointed to the Professorship of Chemistry at University College Galway, where he had a distinguished academic career. (He was retired from UCG when he taught me in TCD.)

Now I can't argue that William Rowan Hamilton should be included in such a roll-call (and I only give a sample) of what might be termed 'traditional' Irish patriots. But I will argue that there are other ways to demonstrate love of one's country. Hamilton would strongly have disapproved of all the rebellions noted above.

At the 1832 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held in Oxford, Hamilton was the 'solitary and youthful representative of Ireland'. In his after-dinner speech there he said:

|

I have spoken of Ireland as my country�.For, however intimate may be the union between your island and mine, and intimate I trust that it may ever be, with an intense and increasing unity, yet the laws of nature and of the mind of man forbid us to expect that there ever can be so perfect a fusion, an amalgamation so absolute, as to leave no sense of distinction; no rivalry, though it be the rivalry of friends and brothers.

|

He had a few days earlier, in a letter to his friend, the poet, William Wordsworth, referring to Ireland, commented: 'I do not look with pleasure on the prospect, now too visible, of a gradual or sudden progress to a Republic, in essence if not in form'. And some years later, in 1837, while travelling through beautiful parts of England, he wrote:

|

I love thy glory, England! Sudden tears

Of an unenvying admiration start, Not seldom, as thy radiant form appears, And the world's stage presents thine honoured past: But Ireland is my birth-place; there youth's years Were passed; my home is there, and there my heart. |

Ten years later, on 6 February 1847, at the height of the Irish famine, Hamilton wrote to his friend Aubrey De Vere:

|

Though I have been giving, and shall continue to give, through various channels, whatever I can spare in the way of money to the relief of those wants, yet I am almost ashamed of being so much interested as I am in things celestial, while there is so much of human suffering on this earth of ours. But it is the opinion of some judicious friends, themselves eminently active in charitable works, that my peculiar path, and best hope of being useful to Ireland, are to be found in the pursuit of those abstract and seemingly unpractical contemplations to which my nature has so strong a bent. If the fame of our country shall be in any degree raised thereby, and if the industry of a particular kind thus shown shall tend to remove the prejudice which supposes Irishmen to be incapable of perseverance, some step, however slight, may be thereby made towards the establishment of an intellectual confidence which cannot be, in the long run, unproductive of temporal and material benefits also to this unhappy but deeply interesting island and its inhabitants.

|

Other commentators held similar views. For example, writing in 1889, and referring to the achievements of Hamilton and his mathematical colleagues in Trinity College, Edward Dowden, who held the Professorship of English Literature at Trinity from 1867 to 1913, wrote: 'to encourage Irishmen to be masters in any and every province is the way to create a true literature in this country, and not to whip them on to a national sentimental purpose'.

And some years earlier, in a letter to Hamilton on 20 September 1841, James Joseph Sylvester (1814�1897), who had just been appointed Professor of Mathematics at the University of Virginia, and later (1883) returned to Oxford as Savilian Professor of Geometry, had made the interesting comment:

|

At a vast distance, and on an humble eminence, I still promise myself the calm satisfaction of observing your blazing course in the elevated regions of discovery. Such national honour as you are able to confer on your country is perhaps the only species of that luxury for the rich�.which is not bought at the expense of the comforts of the million.

|

I don't for a moment wish to minimise the courage and sacrifice of those who, for deeply held motives, fought for Irish freedom. I am very happy to-day to enjoy the fruits of their sacrifices. Of course, the view-point of the privileged upper and middle classes who benefited greatly from the close union of our sister islands was always going to be different from those who found the union oppressive (and these included quite a few of these same higher classes). What I want to do, though, is to suggest that there are other ways to be a patriot. Hamilton, for patriotic reasons, published almost all of his major work in the journals of the Royal Irish Academy, of which he was President from 1837 until 1846, when he could have received quicker fame in journals with a higher international circulation. He loved his country, and determined to carry out what he could do best in order to advance Ireland.

In my book, Hamilton was one of Ireland's great patriots. And those who to-day work hard at scientific research and development in Ireland (especially, of course, those who contribute to The Irish Scientist Year Books!) are continuing Hamilton's concept of patriotism.

Contact: Charles Mollan; E-mail: [email protected]