| 2005 |

|

YEAR BOOK |

University College Dublin

|

Liver fluke attack: new strategy needed

to win the war

|

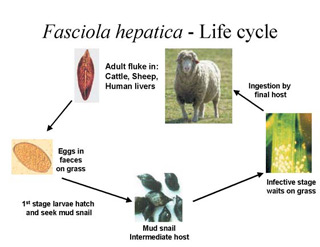

The liver fluke has a complex life cycle. The adult parasite, in the host's liver, is a hermaphrodite (has both sex organs) and lays the eggs. The eggs are passed into the intestines and onto the pasture in the host's faeces. The eggs hatch and the first larval stage emerge. What happens next is crucial to the survival and development of the larvae. These tiny larvae have to find and infect an intermediate host (a mud snail) in order to feed, multiply and grow into the stage that infects cattle and sheep. The larvae are attracted to chemicals released by the mud snail and penetrate the snail's skin. For every one larva that enters the mud snail, up to 600 infective stages can emerge after a number of weeks. These then encyst, for protection from the elements, and wait on the grass (or watercress!) to be ingested by the final host (cattle, sheep, man).

Currently, infected animals are treated with anti-parasitic drugs. Unfortunately, these conventional weapons are becoming redundant due to increasing resistance of liver fluke to these drugs. In the absence of new drugs to combat the resistant fluke, there is a growing need to provide an alternative method of controlling the parasite.

The basic principle of vaccination (e.g. flu vaccine) is that the animal is inoculated, usually with a modified or dead form of the infectious agent. This evokes an immune response, which allows the vaccinated animals to recognise and arm themselves against future attack from the live infectious agent.

Parasite vaccines are more difficult to develop than viral vaccines for two main reasons. Firstly, the most simplistic parasite is at least 12,000 times more complex genetically than a typical virus. In addition, their life cycles consist of a number of structurally diverse stages. This makes effective targeting of the vaccine more challenging.

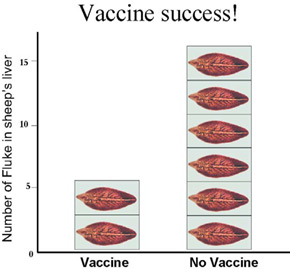

A novel strategy is needed to overcome these problems. The aim of our new 'smart vaccine' is to arm the vaccinated animal, with the ability to cut off the fluke's fuel supply and stop them in their tracks. In order to achieve this, I am investigating how an enzyme, used by the fluke to attack the host, can be turned around and used as a weapon in vaccination. Results so far are promising; we have achieved protection from liver fluke in vaccinated sheep. Their fluke burden was reduced by 66% relative to non-vaccinated sheep.

Further work is necessary to optimise the delivery and route of administration of this vaccine. If successful, this work will provide livestock farmers with a new way of controlling this parasite that is both effective, environmentally friendly and promotes animal welfare. It will also help in the search for effective vaccines to control other parasitic diseases of animals and man.

*June Fanning, Conway Integrative Biology, won second prize in AccesScience '05; a competition for 3rd year postgraduate students held in UCD in March 2005. This is a summary of her presentation .

Contact: June Fanning, MVB, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Parasitology & Conway Institute,

UCD, Belfield, Dublin 4;

E-mail: [email protected]