| 2004 |

|

YEAR BOOK |

University College Dublin

|

'Survivin' breast cancer

|

Breast cancer is the most serious cancer affecting women in Ireland today. Over 1,700 women develop breast cancer in Ireland every year and, unfortunately, almost half of these women will die from their disease. However, the mortality rate for breast cancer is decreasing, due, in part, to both enhanced screening programmes and the development of new and better treatments for breast cancer patients.

The growth of healthy cells is kept in order by a balance between cell growth and cell death � i.e., for every cell that grows, another one dies. Cancer occurs when cells lose their ability to control the balance of cell growth and cell death. For example, when a mutation occurs within a normal cell, the new cancer cell has special properties that allow it to grow very quickly. Normally, this increased cell growth would be counteracted by an increase in cell death. However, cancer cells also receive signals that tell them not to die. This leads to a build up in the number of cancer cells in the breast and eventually to the development of a lump or a tumour.

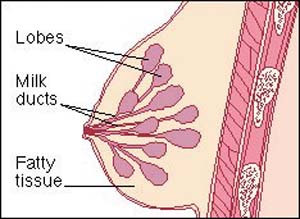

In St Vincent's University Hospital, we are studying the proteins involved in the growth and death of cells, in particular, a protein called 'survivin'. This protein is normally present in the foetus during pregnancy, as it helps to ensure the survival of the foetus until birth. Once a baby is born, survivin is switched off though, in many cancers, survivin is switched back on again, and is thought to be involved in the onset of this disease. The initial aim of our research was to establish if survivin was present in breast cancer.

We found that survivin was virtually absent from normal breast tissues, but was present at very high levels in malignant breast tumours (Figure 2).

The second aim of our research was to determine how survivin may contribute to the development of breast cancer. From a series of experiments carried out by our group, we found that survivin may be involved in driving the growth of tumour cells. It is possible that, when survivin is present in cancer, it sends a signal to the cancer cells that allows them to grow at a very fast rate. As a result, the task of killing these cells with chemotherapeutic drugs is very difficult.

When patients present with breast cancer, doctors are constantly searching for ways of identifying which patients need both surgery and chemotherapy, and which patients need surgery alone � i.e., they are searching for some aspect of the tumour that will tell them how severe the cancer is. Currently, there are few such predictors of aggressive disease. The third aim of our research therefore, was to determine whether or not survivin could be a predictor of poor prognosis. In a study on over 500 breast cancer patients, we found that patients with high levels of survivin had reduced survival times, and were more likely to have their tumours recur. We therefore concluded that survivin was a strong predictor of poor prognosis in breast cancer patients.

Although cancers are often termed under a single heading, for example, breast cancer or lung cancer, each individual tumour can be different in how it forms, progresses, and in how it responds to therapy. This is why we are unlikely to ever find a single cure for cancer. In order to find better drugs for patients with breast cancer, it is necessary to determine how cells lose their ability to control their own growth and death. By doing this, we should eventually understand what causes a normal cell to become a cancer cell. In accordance with this, we have shown that survivin is present at very high levels in many breast cancers, and may be a target for future anti-cancer drugs.

Our research on survivin is just one piece of the puzzle that will provide a greater understanding of how breast cancer develops, and how it can eventually be cured.

* Brid Ryan was one of the winners in AccesScience '04 held in UCD in May 2004. This is a summary of her presentation.

Contact: Brid Ryan, Department of Biochemistry, UCD;

Tel: 01 2094936; E-mail: [email protected]