| 2003 |

|

YEAR BOOK |

University College Dublin

|

Keeping abreast with tumour markers

|

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer amongst women in Ireland. One in 13 women will develop breast cancer before the age of 75 years and nearly half of these women will die as a direct cause of their disease. However, more women than ever before are now surviving breast cancer. This is due partly to the increased awareness associated with breast cancer but also due to advances in screening techniques that aid in the early detection of the disease. Our research team in St Vincent's University Hospital and The Department of Biochemistry UCD is dedicated to identifying new strategies for the early detection of cancer.

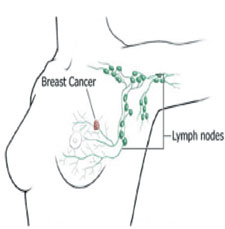

The high mortality rate associated with breast cancer results from the spread of the tumour to other vital organs in the body. Treatment strategies are therefore based on predicting whether the tumour will spread or not. Any cancer cells leaving the tumour will pass through the 'lymph nodes' located nearest the breast (Figure 1). These nodes are tested for certain genes that are said to be specific to cancer cells and therefore mark the presence of cancer (tumour markers). If these genes are detected, the patient is deemed to be node positive and will be given chemotherapy. If none of the genes are detected, the patient is deemed to be node negative and is considered to have a less aggressive form of breast cancer and may be spared chemotherapy. Unfortunately this form of analysis lacks both specificity and sensitivity. Many of these marker genes can be present in healthy non-breast tissue. Furthermore, approximately one third of patients with apparently disease free lymph nodes will develop secondary tumours. So there is a need for more accurate markers of spreading cancer cells.

The search for new and improved tumour markers has identified a novel gene called 'mammaglobin'. This gene has two qualities that suggest it has the potential to be a tumour marker. The first is that it is present in higher amounts in cancer cells compared to normal cells. The second and possibly more important quality is that it is only ever found in breast tissue - this suggests that if mammaglobin was detected in a patient's lymph nodes or blood stream it would indicate the presence of cells leaving the breast, possibly due to the spread of cancer.

Our research group has undertaken the largest scale study to date on the potential of mammaglobin as a breast cancer marker. We have tested over 150 breast cancer patients for the presence or absence of mammaglobin. In addition, we also tested a large number of non-breast tissues for mammaglobin. Our results confirm that mammaglobin is not present in any of the non-breast tissues. This sets mammaglobin apart from any other potential tumour marker to date. Mammaglobin was found to be present in 60% of the breast tumours tested. This means that mammaglobin would be able to detect spreading tumour cells in 60% of patients. This would be a huge improvement on what is currently clinically available. Even though mammaglobin is detecting 60% of breast tumours, it is still missing in the remaining 40% of cases. For this reason, we also tested the same patients for an additional panel of breast specific genes. When we included these genes, our sensitivity of detection increased from 60% up to 84% (Figure 2). Coupled with this is the fact that none of the additional genes were found in any non-breast tissues tested.

* Neil O'Brien was one of the winners in the Merville Lay Seminars held in UCD in March 2003. This is a summary of his presentation.

Contact: Neil O'Brien, Department of Biochemistry, University College Dublin;

Tel: (01) 2094936; E-mail: [email protected]