| 2002 |

|

YEAR BOOK |

BIORESEARCH IRELAND AT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN

|

Navigating publishing, patenting and eternal

damnation in academic biotech

|

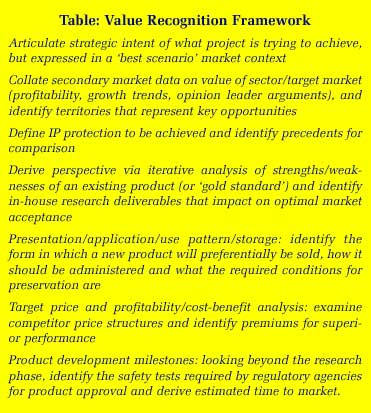

The real value of intellectual property (IP) only makes sense in the context of the price it will ultimately command in the market-place. Here, the patenting basics of industrial utility, novelty and non-obviousness (�to those skilled in the art�) will be tested in the crucible of commerce. However, within life sciences, a clear understanding of market value is often obscured by the long length of product development cycles and the complexity of the regulatory climate. This is also a logistical challenge for technology transfer officers, who work from a generalist base in assisting the commercialisation of a diverse range of technologies, and must summon and project a proprietorial sense of ownership and credible market insight to a potential developer. The process of establishing such a oneness of thought within the university commercialisation team is an asymptotic trajectory that must necessarily be undertaken early in a project. The task for the technology transfer professional must be to close the perception gap between the research bench and the marketplace, giving substance to an evolving intangible asset, and providing a motivational basis for building team cohesion. This is achieved by ensuring that end-user information (see Table) is brought to bear early on in a project, so that the research team can not only view a viable commercialisation (value realization) route, but may also productively incorporate such observations into the research track 1 . Interpretation of research goals against the deficiencies or strengths of an existing product can provide an especially informative benchmark. For example, imparting an early awareness of desired pharmacokinetic criteria (ADMET: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity of a drug) or patient administration requirements (parenteral versus oral route) for a human pharmaceutical can influence target selection, therapeutic approach and compound refinement. Ongoing monitoring of the fluctuating regulatory and political climate in the global market can also reveal both opportunities and threats. The evolution of the BSE testing market within the EU is a good example of this, with a newly uncovered threat to human health in 1996 revitalising post-mortem analysis technology. Similarly, the present moratorium on GM crop cultivation in the EU has seen a burgeoning market in screening for adventitious presence of GM contaminants in foodstuffs.

Adopting a value recognition approach ensures that a �big picture� dynamic is imported into the early stage research perspective, with the ensuing dialogue moving the parties closer to a rationale for cogent and consensual patent-publishing decisions, and perhaps a consideration of more evolved IP protection strategies.

Reference

1. Williams, G.A. (2002), Managing bioindustry � academia collaborations: balancing nurture and nature in the technology transfer equation, Business Briefing PharmaTech 2002, World Market Series, World Markets Research Centre, London, pp. 16�20, ( http://www.wmrc.com/businessbriefing/medicalbriefing/contents/ lifesciences_2002/ )

Contact: Dr Gwilym Williams, General Manager, BioResearchIreland,

Conway Institute of Biomolecular and BiomedicalResearch,

UCD, Belfield, Dublin 4; Tel: +353 (0)1 706 2801;

Fax: +353 (0)1 269 2016; E-mail: [email protected] ;

Web: http://www.biores-irl.ie/